|

|

||||||||||||||||

| HOME ARTICLES GALLERIES ABOUT US FORUM LINKS CONTACT JOYLAND BOOKS | ||||||||||||||||

|

BY THE DOME IT'S KNOWN: A POTTED HISTORY OF SOUTHEND'S AMUSEMENT PARK by Ken Crowe Article: From thegalloper.com, May 2003 |

||||||||||||||||

|

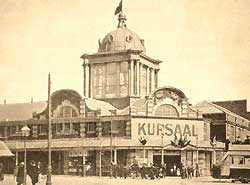

The Kursaal at Southend-on-Sea was the largest amusement park in

the south throughout much of the twentieth century. Historian

KEN CROWE tells us a little about this great place.

|

||||||||||||||||

|

"One

Bright Spot" and "By the Dome it's Known" were

bywords for the Kursaal, certainly in Southend, in

the East End of London and throughout much of

southern England. The Kursaal was the largest

amusement park in the south throughout much of the

twentieth century and the destination for thousands

of East Enders and others up to the 1960s. What does

the word Kursaal mean? According to Hutchinson's

Dictionary of Difficult Words, the term refers to an

entertainment hall, public room or hotel at a spa or

seaside resort. The word is German in origin, and

there are certainly Kursaals on the Continent. There

they are cure-halls - public rooms in spas where the

sick go to recuperate or recover. The word seems to

have been adapted in this country to mean a place of

entertainment, perhaps healthy entertainment, at a

seaside resort. That the word Kursaal has come to be

associated with a place of entertainment, a

'pleasure palace' is illustrated by its use in

fiction; for example, being used in the title of a

Dr. Who book of 1998, in which The Doctor and Sam

travel to a planet being made into a giant pleasure

palace, a Kursaal.

In order to place the building of the Southend Kursaal in its historic context, it is important to mention the, often unfulfilled, attempts to build such pleasure palaces in the later nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries. Attempts to lure the visitor from the nearest large urban centres resulted in a multitude of resort-based entertainment companies, each financed by share ownership, the shareholders often being local businessmen, sometimes entrepreneurs, and sometimes very large concerns with local connections. These limited liability companies planned to build such attractions as winter gardens, piers, towers and Kursaals, but many were unsuccessful. Rarely could enough capital be raised to complete the ambitious projects of their founders and one company frequently gave rise to another, in attempts to carry on the schemes. There was a short-lived Kursaal at Bexhill-on-Sea. Built by the Eighth Earl De La Warr, it was part of his plan to develop Bexhill into a fashionable seaside resort. This Kursaal, established by the Bexhill Kursaal and Winter Gardens Ltd (of 1899), was a pavilion or theatre, and did not house sideshows or amusement machines. There were plans to build a Kursaal at Margate, but these never got off the drawing board. In 1908 the Isle of Wight Kursaals and Entertainments Company was established, and in 1913 the Hove Pier, Theatre and Kursaal Company was formed, but neither of these Kursaals was ever built.

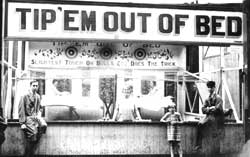

Southend was the nearest seaside resort to London. Following Sir John Lubbock's Bank Holiday Act of 1871, the first Monday in August became a national holiday, and the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway Company posted bills on hoardings all over London advertising Southend as the capital's nearest resort. In 1883 the East London Observer commented: "Everyone seemed to recognise that the August Holiday was, of all others, the one for suburban outings or seaside trips rather than the peculiar enjoyments derivable from parading the streets". On Wanstead Heath the East Ender could enjoy the toy stalls, photographic studios, coconut shies, kiss-in-the-ring, pony and donkey riding, steam roundabouts and swings. Some resorts, Eastbourne and Bournemouth, for example, excluded such amusements, but at Southend such entertainment had been provided, seasonally, for many years on the seafront greens. Southend became known as Whitechapel-on-Sea. When the Marine Park, and then the Kursaal opened, they provided the same sort of entertainments, but this time, bigger and better. The Kursaal remained a major destination, especially for day-trippers and works outings from the East End of London, until the 1960s.There were several annual events for which the Kursaal was justly famous. These included the New Year's Eve Ball, the charity dinner for deprived children, sponsored by the Alexandra Yacht Club, and the Old People's Dinner.

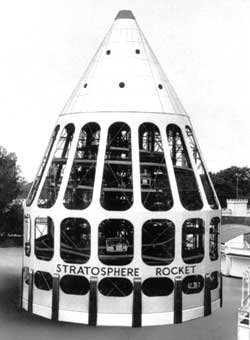

The Kursaal was used as the setting for scenes in a number of films and episodes of television shows, among them The Avengers, The Prisoner, Nearest and Dearest, (when it was supposed to be Blackpool!) and the films Over the Moon and Twenty-One Days. The Kursaal was largely self-supporting, with its own ice-cream and rock factories, greenhouses and laundry. A combination of factors resulted in declining visitor numbers especially from the mid-1960s onwards. Cheap package holidays to the sun, and the growth of sight-seeing tours took a large number of visitors to the Mediterranean or to the West Country, especially following the advent of paid holidays and increased motor car ownership. Southend, like many other large towns, looked towards changing its image in the 1960s, modernising the town centre and seeking a new economic base. Added to that, in the 1960s and 1970s many new entertainment centres were opening in Southend, including the Cliffs Pavilion. Times were changing, but the Kursaal was not changing with them. The closing song There's No Business Like Show Business was played over the tannoy for the last time in the early 1970s. By 1970 the Kursaal fairground was still attracting visitors, but not in the vast numbers of the 1950s and even 1960s. In 1970 the Scenic Railway roller coaster – opened in 1910 – was taken out of service, and in 1971 the Water Chute was dismantled and moved to Ocean Beach Amusement Park at Rhyl (where it still operates to this day).

In December 1972, after standing for three seasons without operating, a fire all but destroyed the Scenic Railway; its charred remains being demolished in early 1973. The decision was taken in 1973 to close the fairground and sell off, in the first phase, 20 acres of the ground for housing. In February 1973 the local press announced that the Kursaal could make way for a skyscraper plan. Plans had been presented first by Utopian Housing and later by Kursaal Estates Limited to the Borough for 750 flats in seven blocks of from 12 to 26 storeys, and 50 three-storey houses, together with pedestrian areas and a leisure complex. A spokesman for the Kursaal was reported as saying that "There is a change in public taste in amusements. It could be that the public are moving away from the fairground atmosphere". The opinion of many of the Councillors was that the Kursaal had become a 'tatty Victorian antiquated fairground'. In January 1974 the owners of the fairground rides had been given notice to quit, and requested to remove their rides at the earliest opportunity. It was in this year that the biggest permanent ride in the park, the Cyclone coaster – which had operated for 37 seasons – was demolished. Outline planning permission was granted for the building of blocks of flats in the Kursaal gardens. In 1977 planning permission had been granted for private housing development over the larger part of the Kursaal gardens or fairground. The Kursaal buildings were placed on the Council's historic buildings list, and in April 1994 the dome and remaining structure were protected by the Grade II listed status by English Heritage. A total of seven bids were lodged with the Council, and in 1995 an agreement was made to lease the Kursaal site to the Romford-based Rowallan Group for the development of a multi-million pound amusement, leisure and conference centre. In February 1998 the building was handed over to the firm of Dean and Bowes for fitting out and in March 1998 the first phase of the restored Kursaal was opened to a specially invited audience. Following many requests to Alan Stack, Chairman of the Rowallan Group, he decided to have a special heritage opening to show the newly restored dome (apparently, 9 skip-loads of pigeon droppings were removed from the dome!) and vestibule, with its ornate plasterwork and stained glass. The event was a great success, and this part of the building then remained open for public inspection and over 6,000 people visited the Kursaal between March and May. |

One bright spot!

|

|||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

THEMAGICEYE | Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy | Contact Us |

||||||||||||||||